Soup is magic. Hear me out on this. At first, the process doesn’t make it sound like you’re going to end up with anything great. Most soups are made with the same basic steps. You heat up some oil or butter and toss around your aromatics — onions, garlic. Add a few of your vegetables — celery, carrots. Pop in some spices. Stir it all around a bit. Add broth and your other ingredients. And then, something happens. A half hour later, your home smells like you could take a bite out of the air and you have enough food to feed a dozen people. It seems logical that we continually show witches stirring something around in a cauldron. Forget potions: it’s soup.

Every culture’s got their own version. There’s pho. Borscht. Harira. Ajiaco. Minestrone. It’s the universal budget stretcher and comfort food. You can freeze the extra for later, or, if you’re me, you can forgo the bowl and just stick your spoon straight in the pot and eat until it’s gone.

Over the course of history, communities around the United States have dabbled in magic. That is to say, while most people might pick out the hamburger as the most distinctly American dish, there’s an argument to be made for soup. We’re soup innovators. Soup aficionados. Dare I say, soup-er-stars. Here are some delicious soups made in America (and stews), how they came to be, and some of the places serving them.

Gumbo

While gumbo has been gracing the pages of cookbooks since the 19th century, and family tables for longer, there’s a bit of disagreement about what makes the perfect gumbo. How thick the base should be. Whether to use shrimp or chicken or sausage. If its origins are Cajun or Creole or Choctaw. However, a few things are for sure. The spicy stew is served over rice, it includes the “holy trinity” of Creole and Cajun cooking — onion, celery and green bell pepper — and it belongs to Louisiana.

The name “gumbo” derives from the Mbundu (the language of the Bantu people of Angola) word for okra, ki ngombo, which is often used as a thickening agent. Along with its West African roots, brought to the country through enslaved people, gumbo incorporates features of French and Choctaw cooking. The stew uses a dark, nutty roux and filé, the ground or dried leaves of a sassafras tree. Most important might be the social aspect of gumbo.

In a 2014 essay in “Religion, Food, and Eating in North America,” scholar Derek S. Hicks wrote of his grandmother’s gumbo, “The gumbo party would start at my house but would ultimately be carried from house to house…until the gumbo pot was empty.”

The best advice, in that case, to enjoy some gumbo in Louisiana might be to make a friend and get yourself invited over for dinner. But if that plan fails, try Dooky Chase’s, Heard Dat and Luizza’s by the Track when in New Orleans.

Clam Chowder

Don’t get mad, Rhode Island, but I’m just going to say it: New England clam chowder is better. While Rhode Island chowder has a clear broth base and Manhattan chowder (blasphemously) uses tomatoes, New England clam chowder is creamy, potato-y perfection. There’s also usually some bacon. Sometimes come celery. Topped with crunchy oyster crackers.

Like the soup itself, its origins are a little murky, but it’s generally agreed upon that French and British sailors in Nova Scotia and the northeast colonies in the United States made versions of a seafood chowder in the 18th century. Whether or not we can say for sure that oyster crackers are the direct descendant of the hard tack bread sailors used in their chowders (okay, they’re not), it feels nice to think so. Over the course of the following centuries, potatoes were added, the cream found its way in, and clams became the most popular main ingredient. And then, like anything from New England, locals became excessively vocal about their allegiance to it.

When in Boston, get yourself a solid bowl of clam chowder at Ned Devine’s or B&G Oysters. Maine Diner in Wells is worth a stop when you’re farther north. Our tip: you should also always try any fresh seafood shack you might find on the coast of Maine. If there’s a fresh lobster roll, there’s probably good chowder too.

Saimin

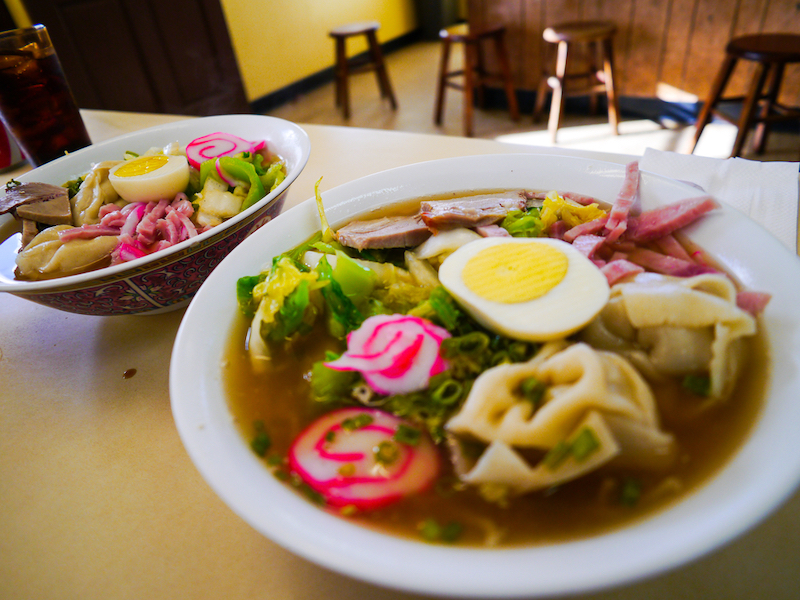

If you look quickly, you might think saimin is a bowl of ramen. Noodles sit in a light broth topped with meat, green onions and the pink and white swirl of kamaboko (Japanese fish cake). But this noodle soup is all Hawaii.

Saimin, like so many other American soups, is the creation of blending cultures. During Hawaii’s plantation boom that started during the mid-1800s, large groups of laborers immigrated from Japan, China, Portugal and the Philippines seeking work. And, while this might be obvious, when people work together, they tend to eat together too. It’s like soup itself — you bring together the ingredients, look away for a minute, and all of a sudden the way the flavors have blended has created something new. Saimin’s broth is lighter than ramen. The noodles are chewy and contain egg, similar to the noodles used in lo mein. Sometimes there’s Spam on top. Ultimately, it is its own thing, and delicious.

Whenever you’re in Hawaii, we recommend you pick up saimin at Palace Saimin in Honolulu, Shige’s Saimin Stand in Wahiawa, or Shiro’s Saimin Haven in Waimalu.

Brunswick Stew and Kentucky Burgoo

If you order a bowl of Brunswick stew or Kentucky burgoo at a restaurant, it probably won’t have squirrel in it. Not anymore, anyway. It used to. These stews are the Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone of soups. In fact, there’s a chance that Daniel Boone himself might have chowed a bowl of burgoo around the beginning of the 19th century. While Brunswick, Ga., and Brunswick County, Va., have long argued over who first introduced their namesake stew to the world, both soups are born out of the ingenuity of necessity: putting what’s on hand into a pot.

It’s likely that both are also adaptations of Native American cooking. Ingredients might vary, but they’re locally available: a tomato broth base, corn, butter beans, potatoes and a meat, which, yes, used to be squirrel or rabbit. Mutton or even opossum might have shown up in a burgoo, specifically. Today, you’re much more likely to get pulled pork or chicken. Both Brunswick stew and Kentucky burgoo are barbecue standbys with dashes of heat and a splash of Worcestershire sauce. Burgoo is a Kentucky Derby staple. Brunswick stew is a favorite of local cooking competitions and fundraisers. These are the gathering soups of Appalachia and the Piedmont. If you’re nearby, here is where you should pick some up to try:

- Burgoo: Old Hickory Barbecue, Owensboro, Ky.

- Brunswick Stew: Fat Matt’s Rib Shack or Fox Bros. BBQ, Atlanta, Ga.

- Buzz and Ned’s, Richmond, Va.

- Clyde Cooper’s Barbeque, Raleigh, N.C.

Chili

This might not be true for Texans, but it feels as though chili has become so ubiquitous throughout the United States that the rest of us sometimes forget that it’s regionally specific. (Like, for example, fajitas.) In fact, it looms so large that we’ve been forced to add the word “pepper” onto the dish’s namesake ingredient in order to differentiate the dish from the curved red vegetable. But let’s not get mixed up about this. Chili is from Texas.

While there are some sources that depict chili’s origins as camp food among cowboys, there’s one group of women largely credited with popularizing the Tex-Mex classic: San Antonio’s Chili Queens. In the 1880s, these entrepreneurs would lug their pots to city squares in San Antonio and cook chili, turning the spaces into open-air markets and selling bowls to everyone who passed through. The version of chili they were selling was a stew with the purity many Texans still strive for: beanless. Despite the lack of legumes, the stands continued for decades, only closing down by the mid-20th century. By that time, the rest of the country had bought in and started adapting recipes — that’s where the beans come in.

Here are a couple places to get some chili in Texas (I know, neither of them are in San Antonio): Texas Chili Parlour, Austin; Molina’s Cantina, Houston.

Cioppino

Cioppino, pronounced chuh-pee-no, sounds like it’s a creation straight out of Italy. It’s the kind of word that might induce someone to hold up their hand like they’re about to snap and do an accent that would embarrass an actual Italian. This impulse is misguided — in more ways than one: the soup’s from San Francisco. Well, okay, Italian immigrant fishermen in San Francisco in the mid-1800s.

For the uninitiated, cioppino is a seafood soup with a tomato broth base, and it is delightfully inexact. If you’re making it at home, any kind of seafood will do. It’s still cioppino. The fishermen used to make the soup on board their boats, tossing in their catch and making something that played off of traditional Italian fish soups like the similarly pronounced ciuppin. The biggest difference between cioppino and those traditional soups makes sense for California: the fisherman added in some chile pepper. You can still get cioppino down by the wharf in San Francisco at Cioppino’s and Sotto Mare.

Broccoli Cheddar

I’m including broccoli cheddar soup not because anyone needs direction as to where to track down the best bowl (it might actually be Panera), or because it’s part of a proud regional history. Rather, its origin story is so incredibly strange and deeply American.

The first thing you need to know is that the first President Bush hated broccoli. Really hated broccoli. According to one researcher, he publicly mentioned broccoli on 70 different occasions. At one point he said to the press, “I do not like broccoli. And I haven’t liked it since I was a little kid and my mother made me eat it. And I’m president of the United States, and I’m not going to eat any more broccoli.” Legend has it that broccoli cheddar soup was born of a response to this hatred. Campbell Soup Co. and Woman’s Day magazine ran a contest called “How to Get President Bush to Eat Broccoli” in 1990 after the release of Campbell’s condensed cream of broccoli soup. They asked for submissions of recipes that featured the soup. They received more than 3,000. With such a large response to the contest, Campbell’s released a cream of broccoli recipe book soon after, which included a recipe for broccoli cheese soup.

This too is the magic of soup. It aims as high as getting a grown man holding the codes to the second-largest nuclear stockpile in the world to also eat his vegetables.

While Panera and Campbell’s might have a stranglehold on broccoli cheddar, if, like former President Bush, you’d like to skip the veggies, here are some places to get some of the beer cheese soup Wisconsin (while not the originators of) is famous for: Miller Time Pub and Milwaukee Brat House in Milwaukee, or The Old Fashioned in Madison, Wis.